https://offcourse.org

ISSN 1556-4975

Published by Ricardo and Isabel Nirenberg since 1998

"DOUBLE-SHOTGUN ON COLUMBUS STREET: A FICTIVE MEMOIR" by Louis Gallo

Every consciousness mutation is apparently a

sudden and acute manifestation of latent

possibilities present since origin.

Gebser, The Ever-Present Origin

There’s old Chin slouched on the concrete steps plucking water chestnuts out of a can. They say he came to America as a stowaway during World War II. He’s about a hundred years old and so skinny his legs have dwindled into two pieces of wire. His khaki pants lie flat on the steps as he eats the chestnuts from Hong Kong Emporium on Decatur Street. They’re poisonous, dad says. Only Chin can eat them because he’s immune. Dad says Chin catches the bus on North Miro, rides up to Esplanade, then transfers all the way to the Quarter. The bus lets him off on Royal Street and he walks over to Decatur.

We wonder how he manages on two pieces of wire. We think maybe he floats. He’s about the most silent old man we’ve ever known. He just sits on the steps slurping those chestnuts. And licorice. Long strings of slimy licorice that look like black spaghetti. Old man Piaggio across the street says the licorice cured him of leprosy. There’s a bowl of sardines beside Chin’s loafers for Quinine, one of the neighborhood cats, a bloated, orange and white tom with one ear missing. Tomorrow we will find him flattened by a car in the middle of the street. He daintily nibbles at the sardines next to Chin’s shoes. We don’t know what smells worse, the shoes or the sardines.

Dad says Chin lost his mind when a rat bit him on the ship to America. No doctor would treat him because he was in stowaway, so the rat disease spread through his bloodstream into the brain. We move toward the steps and whisper, old Chin, old Chin, old Chin, old Chin. His eyes don’t even blink. But every now and then he’ll stretch his purple lips from one end of his face to the other in a contorted grin and say, Jean et Philipe etudiant, or something foreign like that. Then he holds a long strand of licorice above his head by the tip and lets it coil into his mouth. It smears his lips and face black and makes him look like a rotting corpse.

We’re glad we don’t have to get up early because that’s when Peg-Leg roams the neighborhood. Clomp clomp clomp goes the peg, Dad says, a noise we never want to hear.

The little girl on the porch comes later. Her parents moved into the house after Chin died or left the neighborhood, though we kids think he got skinnier and skinnier until he just dissolved. The house isn’t much to speak of, half a house really, like most of the houses on Columbus Street. Shotguns. Our family lives in the right side of the shotgun, Chin and the rest of them in the left. We have three main rooms plus a bath in the middle and a kitchen to the rear. The kitchen window roars with a gigantic, box-like window fan. When it’s hot, Dad puts a block of ice on a shelf behind the blades and you can feel the sweat on your face freeze.

There’s always a yard where generations of animals have been buried. And dusty, stunted banana trees. Sometimes a red pepper bush with peppers so hot their juices can blind you. This happened to Mr. Larry down the street. He picked a red pepper, then rubbed the sleep out of his eyes. The acids corroded his corneas and now he stares into space with eyes that look like the whites of fried eggs. The yards are bounded by high wooden fences that have lost their paint. The boards are gray and soggy like sponge, though we kids still manage to climb them. Sometimes we clutch a piece of soft, rotten wood and come crashing down, and our mothers shout, be careful. So we’re careful for a while and then start climbing again.

The little girl has blond hair and a twisted left foot. She skips rope on the porch as Chin fiddles with and inspects his water chestnuts and licorice. A fat woman rocks on the swing and fans herself with a battered Esso fold-out map. It’s always hot on Columbus Street. The blocks of ice behind the fan help a little. One time the rag man came around with his horse-drawn cart and the horse dropped dead of a heat stroke. Foam bubbled on its bluish lips. The rag man, black as grandma’s stovepipe, wiped the sweat off his brow with his shirt and shook his head. Ain’t it some shame, he mumbled. The rear end of his cart shot up vertically in the air and all the rags and bottles he’d collected scattered everywhere. The little girl sings, One two, buckle my shoe, as she skips rope, Three, four, knock at the door.

The fat woman is her aunt or something. No one knows what happened to the girl’s mother, but the adults whisper about it. We saw the mother once. Her blond hair swooshed around her face like a cloud of light. She was arguing with her drunk and unshaven husband. The bottom half of his face looked rusted. A Checker taxi pulled up and she rushed for it. No one ever saw her again. We call the man her father but we don’t know for sure. He sits on the swing with the fat woman. He wears ribbed undershirts and rolls Target tobacco cigarettes. Our dad smokes Target tobacco too and he rolls better cigarettes. The little girl’s father’s cigarettes look like mangled white worms. Thank God I got my Rosie, he says to the fat woman. She waves the smoke away. She’s just a doll, he says. Too bad her foot curled like that, but no curled foot’s gonna keep the boys away. I just hope I live to see her get married, the fat woman sighs. Her lower arms ripple with blubber. Her flowered sack of a dress is drenched with sweat. You call somebody about those bats? she asks. The man shakes his head. Just ain’t had time, Lo, he says.

We kids hope he never calls. We like the bats. They live in the giant palm tree towering over the house. Dad says it’s half dead. It has no branches at all and only a clump of fronds poke out at the top, where the bats live. At twilight they swarm and make creepy squeaking noises. They’re blind like Mr. Piaggio and emit radio waves so they don’t smash into buildings and kill themselves. They don’t exactly fly, they sort of ricochet about in awkward circles. They’re after mosquitoes and bugs, which is good, because sometimes the mosquitoes are so thick they turn the air sooty. And big – big as ball bearings. Once we slapped one on the back of Jackie’s neck and blood splattered all over our faces. MaMaw says it was a vampire mosquito that would have sucked out Jackie’s blood if we hadn’t crushed it.

At twilight we bring out our flashlights and fly-swatters and go hunting mosquitoes. We put the dead ones in PaPaw’s old wooden cigar boxes. One night we filled fifteen cigar boxes. We thought that would help save the neighborhood, keep some people alive. But the next night the mosquitoes were back and nobody had died and squashing them got boring. Mom sprays us with 6-12 whenever we go outside so we won’t get the sleeping sickness. PaPaw says when he was a boy they brought the yellow fever, Bronze John, he calls it. Dad says it was rats. He says they rolled wooden carts through the streets picking up dead bodies, house after house.

Clomp clomp clomp

That’s around the time the Mafia came looking for PaPaw’s older brother, and they would have stabbed PaPaw too – that’s what they did then, they stabbed you right in the heart – except he begged this black nanny lady to let him hide under her petticoats. Those Mafia guys paced the sidewalk looking for PaPaw and his brother. The brother, Vincent, was already dead, and later some tramps found him drowned in Bayou St. John, his feet embedded in coffee cans full of concrete. PaPaw died in 1974 of senility. He says he still can’t remember what happens from one minute to the next. So we have to keep an eye on him. He sneaks out of the house and wanders around the neighborhood in his underwear. Once Miz Cleezio brought him back and he was stark naked. Nasty old man, she says.

The mosquitoes breed in the swamps and lagoons by the trillions, then fly in and spread the sleeping sickness. This is before the city sent trucks into the streets that sprayed thick, foul gasses to kill insects. Mom says the gas causes birth defects in a lot of children. If you see someone with little flaps for arms, she says, you know they breathed that gas. We don’t want to see anyone with little flaps for arms. We have nightmares about those little flaps.

Five six, pick up sticks. Seven eight, lay them straight.

Sometime we go around the corner to see if Pinhead’s out on his porch. He can’t stand up so his mom and dad carry him out to the swing and let him sit there for hours. He makes horrible sounds, like squawks, and his head tapers up to a point. You can see the point really well because they shave his hair in a crewcut. He wears thick rimless glasses so he can read Joe Palooka comic books, which is about all he ever does. PaPaw says he’s more animal than human. One time PaPaw saw him lunge off the swing and drag himself over to a bowl of dog food. He sucked it up, swinging his head back wildly and licking his lips with every bite. PaPaw makes jokes about it but Pinhead scares us kids.

Like the ones with polio in the special class at McDonogh Nine school. Mom says it’s polio only if they can’t move at all; it’s something else if they jerk around and make seal noises. Muscular disturbance or palsy, she says. She worries it’s catchy and we’ll pick it up if we breath the air around their special room. So we hold our breaths when we pass to get to our classes. Once every year the school has a Mardi Gras parade and the cripples get to ride their wooden wheelchairs in a circle around the cafeteria and throw beads to the normal kids. The teachers pick certain kids to push the chairs. When we get picked, we cringe. We push the chairs with our fingertips and think about nothing else but getting to the bathroom and washing our hands. It’s pretty pitiful because the cripples can’t really throw the beads and trinkets. They just slip out of their hands onto the floor. Most of the kids scramble for the trinkets, but we can’t understand why they would want contact with anything the cripples have touched. So many germs, Mom says. At night she scrubs us down with Dr. Tichenor’s Antiseptic and rubs Vick’s into our nostrils. PaPaw tells her to use Zemo Ointment.

They tore that school down a while back, but kids still march in every morning for class. It went from kindergarten to fifth. There’s about a million McDonogh schools in the city, named after this old miser John McDonogh who left all his secret money to build schools. Sometimes Mr. McDonogh visits the schools. McDonogh unto thee we rear, a monument of lasting wealth. Maybe it’s joy, not wealth. Everybody says something different, but that’s the song we have to sing on school holidays. He’s hunched over, bald and has a bulbous cauliflower nose. He never smiles and munches his lips the way old people do. He just prowls the halls and sometimes looks into a classroom.

Our teacher, Miz Schwander, waves to him, but it’s a fake wave. She wishes he would go back to the tomb or something. He makes her nervous and her armpits sweat and drench her sleeves. Miz Schwander smells like ashes. She eats egg salad sandwiches every day. She calls them sammiches and tells us we should eat them too because eggs are very good for you. You don’t need to eat anything but eggs, she says. Miz Schwander knows someone who eats the grass in her back yard. She never mows the grass because she eats it instead, on her hands and knees grazing like a cow. Sometimes she licks the stalks of sugar cane and bamboo that shoot up from a broken sewer pipe in her yard. We would like to see that, we tell Miz Schwander, but she laughs. Honey, it’s too sad, she says. And it’s my aunt Lucille. I won’t embarrass her. She’s not cuckoo or anything, she just likes the way grass tastes. She works at Charity Hospital emptying bedpans and changing bandages. She might lose her job if they find out.

She’s the one who told me about your PaPaw, the time he liked to hemorrhage to death after his hernia operation. He was still a really young man when his mama found him bleeding in the alley and she started to scream. Dr. Johnny came running over and gave him a shot in one of his veins. Dr. Johnny said it was coffee in that shot. I didn’t ask him what brand but I happen to know he likes Community Coffee with chicory. It’s what saved your PaPaw’s life that time, Miz Schwander said. The coffee got his heart beating again. It perked him up long enough to get him to Charity in an ambulance. Lucille told me. She changed your PaPaw’s bedpan. One time he got so nauseated he ran to the bathroom and threw up a big green tapeworm right on the shower stall floor. Lucille cleaned it up. She said the tapeworm was seven inches long and fuzzy. That’s what ailed him, she said.

I don’t like it when Dr. Johnny tries to kiss my mom. Whenever we get sick and he comes over with his black bag full of medicine and instruments, my sister and I catch him trying to kiss her. She always smiles and pulls away, saying softly, Stop it, Johnny, it’s not right. But he always comes back and Ruthie and I decide it’s better not to think about it. We never tell Dad, and I bet Mom doesn’t either. I don’t think Dr. Johnny likes our dad. Whenever they talk, Dr. Johnny smirks and yawns a lot and tries to get away as soon as he can. But Dad loves Dr. Johnny. He wants to talk to him about everything all the time. He likes to talk about short wave radio and history and geography. That’s Dad. He can talk forever. Sometimes he talks to trees and the fence and even his black pickup truck. He talks to old Chin for hours at a time, or what seems like hours; when you’re a kid one minute can seem like hours.

Chin just sits on the steps and swallows another water chestnut. And the little girl Rosie skips rope on the pavement. Nine ten, the big fat hen. The rag man passes with his cart, crying, rags, paper, bottles. And sometimes you can hear Pinhead squawking around the corner. He didn’t live long. He died last year. But we still hear him, and when we ride bikes past his house, there he is on hands and knees, gobbling down the wet, ugly dog food. We shouldn’t stare at Pinhead but can’t stop ourselves. Mom says whatever’s wrong with him is much worse than polio. We kids think maybe a mosquito bit him.

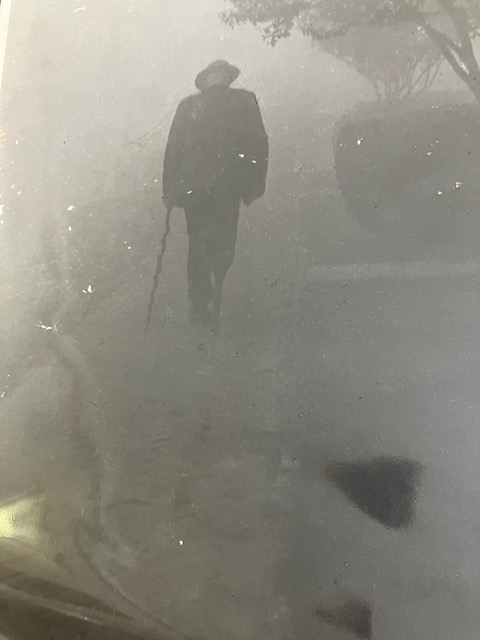

Bromoil photo by "Dad" (Liberato L. Gallo), ca. 1955

Peg-Leg clomps through the neighborhood every morning. Dad says he’s a ghost.

We don’t like Miz Cleezio much because whenever she visits MaMaw she sits at the kitchen table and giggles so much that she pees on herself and it drips and puddles on the linoleum floor. The window fan roars and drowns out our voices. MaMaw curses after she leaves and cleans up the mess. She says Miz Cleezio is feeble-minded. Miz Cleezio died of stomach cancer in 1958, but sometimes she still finds PaPaw roaming the neighborhood and guides him back to us. So MaMaw invites her over for tea and lady fingers and she pees again. She stuffs the lady fingers into her mouth until her cheeks bulge and when she talks, crumbs spray everywhere. The fan roars, the little girl sings, eleven twelve, the fat lady lugs the father’s body up concrete steps. We don’t know if he’s drunk or dead.

The fat lady takes care of Rosie now, but she’s grouchy and always complains that it’s not her child, why should she do all the work? Old Chin howls like a mad man when he runs out of water chestnuts. Sometimes our mom picks them up for him at the Hong Kong Emporium. It’s right next to Central Grocery where she goes to buy Romano cheese and ravioli shells. The smells of Central Grocery almost make you faint: anise, salami, garlic, mint, coffee beans, cheeses, rotting bananas – all mixed together. The aromas saturate our clothes and skin, and we all smell like the grocery for days. Mom buys the ingredients for ravioli, but PaPaw rolls out the meat and cow brains and tomato sauce and cheese into a big slop on the kitchen table and stuffs the pasta shells. He says the cow brains are for texture. We kids don’t think about the cow brains when we eat ravioli. It’s a big treat, twice a year, at Thanksgiving and Christmas. It’s delicious, but if we thought about the brains, we wouldn’t eat it. Once we made old Chin try to eat one and he smelled it for about an hour. He put it in his mouth, chewed, swallowed and then vomited. No one cleaned up the vomit, and soon the ants crawled all over it.

MaMaw says ants save us from rats and possums that also like to eat vomit. She says Chin should climb back into his grave. And that poor little girl, she says, now that she’s got no father or mother. The fat lady just sits on the back steps drinking glasses of baking soda and water. She belches and retches and sometimes spits up in the galvanized pail beside her. Dad says she has dyspepsia. She lets Rosie run around with no clothes on. Rosie rolls around in the dirt in the back yard like a filthy animal. That’s what the fat lady calls her, filthy animal. She says nobody will marry her now. That’s when Rosie started bleeding from the hands and biting people. Some people had to come and take her away. Mom says they put her in the Home for the Incurables. But she still skips rope as if nothing happened. Thirteen, fourteen, maids are courting. We kids think maybe Pinhead will marry her. Secretly, some of us would like to marry her, even with the twisted foot. Her face looks like a valentine when it’s clean, and her hair, like glowing fresh straw. Sometimes grown men stare at her and fall to their knees. PaPaw says maybe she’s one of those girl saints who become angels.

They come in a special white limousine to take Rosie away, just when the bats in our palm tree streak down to attack PaPaw’s hair. He swats at them with his folded newspaper, rips out the claws from his head and collapses on the porch. We’re in the back yard, burying Dickie, our parakeet, but we hear PaPaw screaming. There’s only one bat left when we get there, and PaPaw tries to choke it to death as it hisses and screeches. His head is bloody and scratched and he worries about rabies. The bats chewed off all of his hair and it never grows back. Now he wears a black beret and sits on the porch swing and shoots the bats one by one with a b-b rifle. He’s killed about five, but mostly the b-b’s only stun them, they drop out of the tree, then fly back up. If they are still wriggling on the banquet, PaPaw drops a brick on them, scoops them up with a shovel and hurls them into the garbage cans up front. Every time PaPaw kills a bat the mosquitoes regroup and attack us. MaMaw fusses and screams at him to stop shooting the bats but he won’t listen. They took my hair, he growls.

Old Chin laughs because he’s never had any hair since the day he was born. The rag man curses because the mosquitoes make his horse sick, and by evening we kids are swollen with itchy welts. Mom slathers on the Dr. Tichenor’s but we scratch and scratch. MaMaw swats our hands when we scratch. She says we’ll get red streaks from blood poison and when the red streaks reach our hearts, we’ll die. Sidney Roveri around the block had a red streak that inched up from his wrist to his elbow. Every hour he marked the spot where the streak ended with a ball point pen to see how fast it was moving. When it reached his shoulder, they took him to Charity. We don’t know what they do to him, but he comes back white as an onion and stays that way. And a chunk of his arm is missing. Then the city sprays gas to kill the mosquitoes and MaMaw stops fussing at PaPaw for shooting bats.

Dad’s the one who wakes up before everyone, early in the morning when fog from the river rolls through the streets like clouds of bundled laundry. He teases us with stories about Peg-Leg, the old pirate who once sailed with Jean Lafitte. Peg-Leg wears a long, tattered, gray coat and wraps a faded red bandana around his head. A golden loop made by the Spanish conquistadors dangles from his left ear, and he has a black patch over one eye. A canon ball took one of his legs, so he made himself a new leg from a cypress branch and attached it to his stump with strips of rag and rope. Dad says you hear him coming before you see him. Clomp clomp clomp. Peg-Leg has a girlfriend in the neighborhood and Dad says he still loves her and is trying to find her. When he was younger, he docked his ship at a Mississippi wharf and rode his horse right off the gangplank to the neighborhood. Now he’s old and can’t ride horses anymore, especially with the stick leg. So he takes his time.

We don’t want to believe Dad and punch him on the arm whenever he talks about Peg-Leg. He tells us to get up early with him and he’ll prove it. He even promises to take a picture of him with his Leica. We don’t like to get up early when there’s still fog, but mostly we’re worried Dad is right. He always calls us chickens, so one of us finally works up the courage to get up early and hide with him in the azalea bush up front. The rest of us stay inside, though on that morning, we’re far from asleep as we lie in our beds waiting to hear about what happens. It’s so early dew coats the grass and leaves of the azalea bush. It’s too early for Chin to be sitting on the steps. Too early for the little girl Rosie to skip rope. Too early for the rag man to come round. So Dad and one of us squeeze into the giant bush, Dad with the Leica hanging from his neck, and we wait and wait and wait in the fog. It’s damp and a little chilly and squatting is uncomfortable.

The boy who isn’t afraid gets tired and wants to go back to bed. Just a little longer, Dad says, pressing a finger across his lips. If he thinks we’re here, he won’t come. And right then we think we hear something in the distance, like when MaMaw pokes her broom handle on the back yard bricks. A faint clomp. Then louder, clomp clomp clomp, louder and more ominous with every step. All at once the boy beholds the breath-taking sight of Peg-Leg emerging out of the fog, limping down the sidewalk right in front of our house. He looks exactly the way Dad described him. The boy trembles, feels his blood turn to ice, and he wants to dash away, run forever. But Dad wraps an arm around him and forces him down. Shhhh, he whispers. And now Peg-Leg passes directly before the bush, so close we can reach out and touch his wooden leg. We feel his putrid, fire breath on our necks. It smells like seaweed, rotten fish, ocean salt. Dad won’t release his grip on the boy until Peg-Leg takes a few more steps down the street and begins to recede into the fog again. Then he rises from the bush, focuses his Leica and snaps a picture. Peg-Leg hears the shutter click and slowly turns to inspect us. The boy won’t look. Dad says later that Peg-Leg fixed his good eye on him and it burned. He opens his shirt and shows us the bruised-looking scar near his shoulder blade. But I got the picture, he laughs. Now they’ll believe me.

At the turn of the century, a boy - the one who wasn’t afraid - crawls on his knees through a dusty attic laced with oily cobwebs. He roots through a box of musty papers stored in his sweltering attic and comes across the faded black and white photograph of Peg-Leg. His heart goes wild. Dad, who died in 1986, climbs the attic stairs to join him. I told them he was real, Dad says. We gaze at the picture together. You don’t see Peg-Leg’s face, just a full-length shot as he hobbles away from the camera. But the wooden leg is unmistakable, and the bandana and earring. It seems to the boy, now a man fast approaching the age of his father when he died, that, despite the evidence, despite the photograph, Peg-Leg could not have existed, was merely one of the stories his father told. And Chin too and the bats and Rosie and maybe the entire preposterous neighborhood. His father looks sad. Why would you think that? he asks.

The boy too wonders why such a thought would have occurred to him to him. He . . . we, know the neighborhood is real. Pinhead still rocks on his swing, bobbing his head up and down like a broken piston. Quinine finishes off the putrid sardines. There’s Rosie skipping rope again, her leg still twisted. She starts over. One two, buckle my shoe. PaPaw shoots another bat. The city has not yet sent trucks in to spray the mosquitoes, so MaMaw tells him to stop. We’ll all get the sleeping sickness, she growls. Rosie’s drunken father lies flat on his back on the pavement. The fat woman drags him up the steps. She swallows a glass full of bubbling baking soda and water. We laugh when we hear her belch and make belching noises ourselves. Brats, she mumbles. Old Chin has died. Dr Johnny tries to kiss our mother, and she pushes him away, but she smiles too. Why does she smile? PaPaw and MaMaw have also died. MaMaw tells Miz Cleezio that she can’t come over anymore unless she stops peeing on the floor because guess who has to clean it up.

Our parakeet Dickey flies into the window fan and all that’s left of him is a few yellow feather floating in the air. We’re crying as we bury one of the feathers in the back yard next to Quinine’s grave. There must be a million animals buried in the back yard. Mr. Piaggio roots in the gutters for pennies and bottle caps. This is before the red pepper juice blinds him. Miz Schwander tells us to eat egg salad sandwiches. She shoos Mr. McDonogh out of the classroom. Time to sing, she laughs. “O Come All Ye Faithful,” since it’s near Christmas time.

We want new bikes, a basketball, new baseball bats, dolls, teddy bears, a stick horse. One of us wants a camera, a real camera, like Dad’s, because, he says, you never know who won’t believe you. Still exploring the attic on the eve of the millennium, he begins to suspect that time has played an enormous trick on everyone. He and his mother and sister are the only ones left now, the sole survivors of the past, of a neighborhood that once flourished briefly, on Columbus Street. It seems that the intervening years, not the neighborhood, are what’s illusory. This other time, this new era, is alien and uncomfortable, a shoe size too small. But still Miz Cleezio giggles and pees and MaMaw curses as she wipes it up with a rag.

PaPaw is missing again. They’ll find him two or three blocks away and bring him back. They took my hair, he fumes. And one of us listens for Peg-Leg with Dad. Peg-Leg, the man in the attic realizes, is Death, not the people dying one by one, Pin-Head, Mr. Piaggio, PaPaw’s brother and all the rest, not single, feeble deaths, obituaries, but something broader, more majestic, winding though the streets like an endless strand of foggy licorice that you can eat. It may poison you, and they’ll rush you to Charity in bustling panic because the red streak inches toward your heart; you’ll come back white as an onion with a chunk of flesh missing . . . but you’ll come back. Or maybe you won’t.

The little boy who gets a camera for Christmas tells Chin to smile and say “cheese.” At the bottom of the picture you see only the top of Quinine’s head, that one ear stretched back as if he’s attuned to some faraway sound, something we can’t hear. Chin’s face is smeared with saliva and licorice, and bloodied water chestnuts fall out of his mouth like the Eucharist. Just as the boy presses the shutter, he finds another dusty old photograph in the box, the one he took. But it’s blank, now the color of parchment and, he remembers, the color of the sky that particular morning. The emulsion has cracked into a spidery web of veins and flakes off the paper. Chin smiles and says something foreign. Fromage. PaPaw shoots himself in the toe and howls. We never see Peg-Leg again, or hear the clomp, because, Dad says, he found his girlfriend and she knows voo doo and makes him young again. The man in the attic throws back his head and a cobweb enmeshes his face. I’d like some of that voo doo, he laughs, spitting out soft knots of gossamer. And because you never know who’ll believe you, he stretches out his arms and aims the camera at his own face.

Seven volumes of Louis Gallo’s poetry, Archaeology, Scherzo Furiant, Crash, Clearing the Attic, Ghostly Demarcation & The Pandemic Papers, Why is there Something Rather than Nothing? and Leeway & Advent. His work appears in Best Short Fiction 2020. A novella, “The Art Deco Lung,” appears in Storylandia. National Public Radio aired a reading and discussion of his poetry on its “With Good Reason” series (December 2020).His work has appeared or will shortly appear in Wide Awake in the Pelican State (LSU anthology), Southern Literary Review, Fiction Fix, Glimmer Train, Hollins Critic, Rattle, Southern Quarterly, Litro, New Orleans Review, Xavier Review, Glass: A Journal of Poetry, Missouri Review, Mississippi Review, Texas Review, Utopia Science Fiction Magazine, Baltimore Review, Pennsylvania Literary Journal, The Ledge, storySouth, Houston Literary Review, Tampa Review, Raving Dove, The Journal (Ohio), Greensboro Review, and many others. Chapbooks include The Hymn of the Mardi Gras Flambeau, The Truth Changes, The Abomination of Fascination, Status Updates and The Ten Most Important Questions of the Twentieth Century. He is the founding editor of the now defunct journals, The Barataria Review and Books: A New Orleans Review. His work has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize several times. He is the recipient of NEA grants for fiction and Poets in the Schools. He is now Professor Emeritus at Radford University in Radford, Virginia. He is a native of New Orleans.